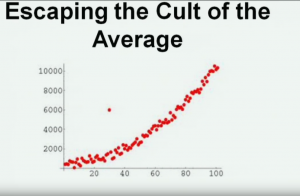

I recently stumbled on Shawn Achor’s Ted Talk about Happiness. I immediately liked what he presented when he talked about the Cult of the average in psychology.

What the cult of the average does is, in simple terms, ignore the outliers in our data. Actually in psychology for many years attention was paid to the outliers, but to the negative ones. That is until Martin Seligman popularized positive psychology. Martin said something like, “Let’s not only look at the negative, let’s also look at the positive outliers.

The reason why we want to look at the positive outliers, the people who are the happiest, most successful, is because they represent the potential. Studying them can teach us how they got there, and applying that knowledge to the rest of us can have immensely positive outcomes. So since Shawn also wrote a book, I naturally had to read it. Let me quote and explain the parts of Shawn’s book I most like.

Positive psychology at work

Most people believe that if they are successful, they will eventually become happy. This formula has been thought to most of us by schools, parents, society or companies. It turns out this formula is flawed. To know why let’s apply common sense first and then look at the studies. If success means happiness, why then are there so many unhappy people which by today’s standard of success, should be happy? And why are many people living in (today’s standards) poverty so happy?

More than a decade of research in psychology and neuroscience has shown that the relationship between success and happiness works the other way around. It turns out that happiness is the precursor to success. Happiness and optimism fuel performance, leading to better outcomes. While waiting to be happy limits our brain’s potential for success.

The effects of depression

A 2004 Harvard Crimson poll found that 4 in 5 Harvard students suffer from depression at least once during the school year and nearly half of them from depression so severe that they can’t function.

When Shawn first entered Harvard he observed a common pattern among the students. First, they would be excited about their privilege to study at Harvard, but soon they would frett incessantly about their future, competition, workload, and stress. Not only the most negative students have a negative mindset, their academic performance was affected most.

In 2006, Dr. Tal Ben-Shahar opened what would become Harvard’s most popular course, Positive Psychology 1504. Over 1200 students enrolled in the first semesters, Shawn and his colleagues realized that students were there because they were starving to be happier.

The students were highly intelligent and had mastered some of the hardest academic courses, but they hadn’t been thought how to maximize their brain’s potential to find meaning and happiness.

The power of happiness

Let’s fly very briefly through some very interesting studies. As I said, studies in psychology and neuroscience have shown that we become more successful when we are happier. For example,

- Doctors put in a positive mood before making diagnosis show almost three times more intelligence and creativity than doctors in a neutral state and they make accurate diagnoses 19% faster.

- Optimistic salespeople outsell their pessimistic counterparts by 56%.

- Students primed to be happy before taking math achievements tests far outperform their neutral peers.

It seems that our brains are hardwired to perform the best in a positive state. The positive state we are talking about (Happiness) is defined as the experience of positive emotions — pleasure combined with deeper feelings of meaning and purpose.

Some studies

One study measured the initial level of positive emotions in 272 employees, then followed their job performance over the next 18 months. They found that those who were happier at the beginning ended up receiving better evaluations and higher pay later on. [1]

Another study found that how happy individuals were as college freshmen predicted how high their income was nineteen years later. [2]

An impressive longitudinal study looked at 180 nuns born before 1917. They were asked to write down their thoughts in autobiographical journal entries. Five decades later a group of researchers coded the entries for positive emotional content. The nuns whose entries were more joyful content lived nearly 10 years longer than the nuns whose entries were more negative or neutral. [3]

Your brain on happiness

More happiness means a broader, more thoughtful and creative ideas. The opposite what a fight or flight response of an overstressed brain produces.

Individuals who are primed for an amused mindset by scientists before an experiment can think of a larger and wider array of thoughts and ideas than individuals who feel either anxiety or anger.

When we have positive emotions our brains get flooded with dopamine and serotonin, chemicals that make us feel good and interestingly, dial up the learning centers in our brains so that we can organize new information, keep information in the brain longer and retrieve it faster later on.

They also enable us to make and sustain more neural connections which in turn allows us to think quickly and creatively, become more skilled at complex analysis and problem solving and see and invent new ways of doing things.

Some more studies

Positive emotions can open our eyes to new solutions and ideas from a very young age as one experiment where researchers asked four-year-old children to complete a series of learning tasks such as putting together blocks of different shapes.

One group received neutral instructions while the second group was asked to think briefly about something that makes them happy, before working on the exact problem as the first group. These kids most likely hadn’t a whole lot of happy experiences to choose from at age four, but still, the children who were primed to be happy significantly outperformed the others by completing the task more quickly and with fewer errors. [4]

This effect does not just appear in children, for instance, students who were told to think about the happiest day of their lives right before taking a standardized math test outperformed their peers. [5]

People who expressed more positive emotions while negotiating business deals did so more efficiently and successfully than those who were more neutral or negative. [6]

In one surprising study divided experienced doctors into three groups. One group was primed to feel happy, the second one was given neutral medicine-related statements to read and the third group formed the control group. The goal was to see how fast they would perform the correct diagnosis while avoiding anchoring (something that occurs when doctors have trouble updating their initial diagnosis in the face of new information).

On average, the doctors primed for happiness not only performed the diagnosis nearly twice as fast as the control group, they also showed two and half times less anchoring. [7] And it didn’t take a lot to make the doctors happy, there was no cash reward, the doctors were primed with candy! Even small shots of positivity can give us a significant competitive advantage.

After seeing so many benefits of happiness, the next thing useful to know is, how can we capitalize on it?

Capitalizing on happiness

The first thing to understand is that happiness is not a mood, it’s a work ethic. It was once thought that happiness was almost completely dictated by genetic heritage. But since, scientists have discovered that we have far more control over our own emotional well-being than previously believed. [8]

What this means is that even if our happiness baseline fluctuates around on a daily basis, with a concerted effort we can raise that baseline permanently so that when we are going up and down, we are doing so at a higher level.

Meditate

Neuroscientists have found that monka who spend years meditating actually grow their left prefrontal cortex, the part of the brain most resposible for feeling happy.

You don’t need to meditate for years to reap the benefits though, 10 to 20 minutes a day can have a big positive impact. Studies have shown that we experience more feelings of calm and contentment right after meditating. As well as heightened awareness and empathy.

Regular meditation can permanently rewire the brain to raise levels of happiness, lower stress and improve immune function. [9]

Find something to look forward to

One study found that people who just thought about watching their favorite movie actually raised their endorphin levels by 27%. [10] Find something you can feel positive anticipation for, it is one of the most enjoyable parts of any activity.

Commit conscious acts of kindness

Long empirical research including one study of over 2000 people has shown that acts of altruism — giving to friends or strangers — leads to enhanced mental health and decreases stress. [11]

Sonja Lyubomirsky, a leading researcher and author of the book The How of Happiness, has found that individuals told to complete five acts of kindness over the course of a day report feeling much happier than control groups and that the feeling lasts for many subsequent days after the exercise is over. [12]

Infuse positivity into your surroundings

Our environment can have an enormous impact on our mindset. While we don’t always have complete control over it, we do have the power to infuse it with some positivity. A good example of the positive effect of an environment is a study that found that people who spend 20 minutes outside in good weather get a positive boost in their mood and also broadened thinking and working memory. [13]

Watching less TV is also not a bad idea. Psychologists found that people who watch less TV ironically are more accurate judges of life’s risks and rewards. [14]

Practice gratitude

Psychologist Robert Emmons has spent nearly his entire career studying gratitude. He found that few things in life are as integral to our well-being. [15]

There are countless studies that show that consistently grateful people are more energetic, emotionally intelligent, forgiving, and less likely to be depressed, anxious and lonely.

And it’s not that people are only grateful because they are happier. Gratitude has proven to be a significant cause of positive outcomes. When researchers pick random volunteers and train them to be more grateful over a period of a few weeks, they become happier and more optimistic, feel more socially connected and experience a better quality of sleep while having fewer headaches than control groups.

Practice optimism

Optimism is a tremendously powerful predictor of work performance. Studies show that optimists set more, and more difficult goals, stay more engaged in face of difficulty and rise above obstacles more easily than pessimists. Optimists cope better in high-stress situations and are able to maintain higher levels of well-being during hardship.[16]

Richard Wiseman proved in a clever way that expecting positive outcomes actually make them more likely to arise.

Wiseman studied why some of us seem to be consistently lucky while other’s don’t. [17] It turns out that it comes down to whether people think they are lucky. Wiseman demonstrated this by asking volunteers to read through a newspaper and count how many photos were in it. The people who claimed to be lucky took mere seconds to accomplish this task, while the unlucky ones took an average of two minutes.

Why? Because on the second page a large message read: “Stop counting, there are 43 photos in this newspaper.” But it gets even better, halfway through the newspaper was another message that read. “Stop counting, tell the experimenter you have seen this and win $250.”

The people who had claimed to be unlucky looked right past this opportunity. The opportunities were latent in everyone’s environment, it was just a matter of whether or not people picked up on them. If we think we are lucky we are more likely to pick up on those events. Think of the consequences this can have on your career and life in general. 69% of high school and college students report that their career decisions depended on chance encounters. [18] Psychologists call priming yourself for opportunity “predictive encoding.”

So how can we best capitalize on this phenomenal principle? Again, by regular practice and training. The best way to kick-start gratitude and optimism is by making a daily list of the good things in your career, job, and life in general. You might think, well that sounds a little hokey, but over a decade of empirical studies have proven the profound effect it has on the way our brains are wired. And you don’t want to dismiss so much research, at least I don’t 😉

So write down those “3 good things” that happened today, this will train your brain to scan for the positive.

One study found that participants who wrote down three good things each day for just one week, were happier and less depressed at one-month, three-month, and even six-month follow-ups.

Even after stopping the exercise, they remained significantly happier and showed higher levels of optimism. The better they got at scanning the world for good things to write down, the more good things they saw even without trying.

A good variation of the “three good things” exercise is to maintain a short journal entry about a positive experience. Researchers Chad Burton and Laura King have found that journaling about positive experiences has at least an equally powerful effect.

One of their experiments in which people who were instructed to write down positive experiences for 20 minutes, three times per week, showed that they experienced larger spikes of happiness, and even fewer symptoms of illness three months later, compared to a control group that wrote about neutral topics. [19]

Personally, I like to journaling because it gives me a way to analyze events and plan for the future.

So there you have it, this is only a fraction of the information and value you will get out of this book, which is one of my favorites. So I can only recommend you get it.

Click here to buy the book on Amazon

Resources:

- Staw, B., Sutton, R., & Pelled, L. (1994). Employee positive emotion and favorable

outcomes at the workplace. Organization Science, 5, 51–71. - Diener, E., Nickerson, C., Lucas, R. E., & Sandvik, E. (2002). Dispositional affect

and job outcomes. Social Indicators Research, 229–259. - Danner, D., Snowdon, D., & Friesen, W. (2001). Positive emotions in early life and

longevity: Findings from the nun study. Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, 80, 804–813. - Master, J. C., Barden, R. C., & Ford, M. E. (1979). Affective states, expressive

behavior, and learning in children. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology ,

37, 380–90. - Bryan, T., & Bryan, J. (1991). Positive mood and math performance. Journal of

Learning Disabilities, 24, 490–494. - Kopelman, S., Rosette, A. S., & Thompson, L. (2006). The three faces of Eve:

Strategic displays of positive, negative, and neutral emotions in negotiations.

Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 99, 81–101. - Estrada, C. A., Isen, A. M., & Young, M. J. (1997). Positive affect facilitates

integration of information and decreases anchoring in reasoning among physicians.

Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 72, 117–135. - Lyubomirsky, S., Sheldon, K., & Schade, D. (2005). Pursuing happiness: the

architecture of sustainable change. Review of General Psychology , 9, 111–131. - Shapiro, S. L., Schwartz, G.E.R., & Santerre, C. (2005). Meditation and positive

psychology. In Snyder, C. R., & Lopez, S. J. (Eds.), Handbook of Positive

Psychology (pp. 632–645). New York: Oxford University Press. - (April 3, 2006). Just the expectation of a mirthful laughter experience boosts

endorphins 27 percent, HGH, 87 percent. American Physiological Society.

Retrieved at www.physorg.com/news63293074.html. - Post, S. G. (2005). Altruism, happiness, and health: It’s good to be good.

International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 12, 66–77; Schwartz et al. (2003).

Altruistic social interest behaviors are associated with better mental health.

Psychosomatic Medicine, 65, 778–785. - Lyubomirsky, S. (2007). The How of Happiness . New York: Penguin, at 127–129.

- Gerber, G. L., Gross, et al. (1980). The “main-streaming” of America: Violence

profile no. 11. Journal of Communication, 30, 10–29. As cited in Barbara

Fredrickson’s Positivity, at 173. - Babyak, M., Blumenthal, J., Herman, S., Khatri, P., Doraiswamy, P., Moore, K.,

Craighead, W., Baldewicz, T., & Krishnan, K. (2000). Exercise treatment for major

depression: Maintenance of therapeutic benefit at ten months. Psychosomatic

Medicine, 62, 633–638. - Emmons, R. A. (2007). Thanks! How the New Science of Gratitude Can Make

You Happier. New York: Houghton Mifflin. - For a sampling of the extensive scientific literature on optimism, see: Carver, C.

S., & Scheier, M. F. (2005). Optimism. In Snyder, C. R., & Lopez, S. J. (Eds.),

Handbook of Positive Psychology (pp. 632–645). New York: Oxford University

Press; Scheier, M. F., Weintraub, J. K., & Carver, C. S. (1986). Coping with stress:

Divergent strategies of optimists and pessimists. Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, 51, 1257–1264. - Wiseman, R. (2003). The luck factor. The Skeptical Inquirer, 27, 1–5.

- Bright, J. E., Pryor, R.G.L., & Harpham, L. (2005). The role of chance events in

career decision making. Journal of Vocational Behavior , 66, 561–576. - Burton, C., & King, L. (2004). The health benefits of writing about intensely positive

experiences. Journal of Research in Personality , 38, 150–163.